This is one of the most profound books I’ve ever read. Stemming from both (Zen) Buddhist and Taoist philosophies, it discusses the artless art, action through non-action, and beauty in the mundane. It brings to life the inner world of one’s own consciousness. Its main focus is to help the individual release the ego, allowing us to work from our natural, unconscious flow state. This is something athletes call being in the zone, but its concepts can easily be extended to both our personal lives and careers. In being unattached to the results in life, we learn to apply ourselves fully to perform our most authentic, passionate, and paradoxically, best work yet.

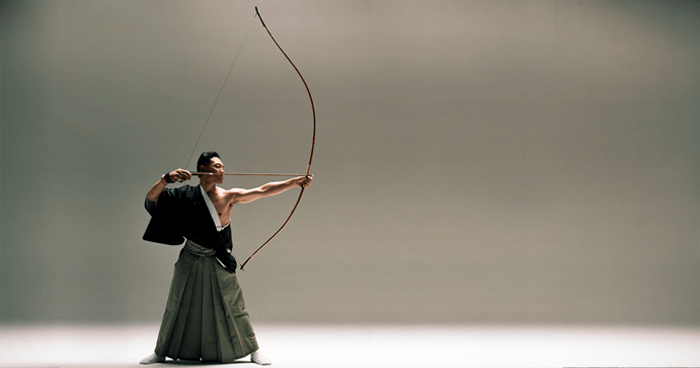

The book itself recounts the experiences of a german philosophy professor, Eugen Herrigel, and his wife who travel to Japan in the 1920s to study zen in various forms of art. His wife takes up flower arranging and he begins the study of Kyūdō, a style of Japanese Archery. This book is said to have introduced Zen to the West in the late 40s. Let’s dive in…

The mind must first be attuned to the Unconcious. If one really wishes to be the master of an art, technical knowledge of it is not enough. One has to transcend technique so that art becomes an “artless art” growing out of the unconscious. In the case of archery, the hitter and the hit are not opposing objects but are one in reality. The bow and arrow are actually just a pretext for something that could just as well happen without them. They are only the way to a goal, not the goal itself. Only the truly detached can understand what is meant by “detachment,” and that only the contemplative, who is completely empty and rid of the self, the ego, is ready to “become one” with the “transcendent deity.”

When drawn to its fullest extent, the bow encloses the “All” in itself, explained the master, and that is why it is important to learn how to draw it properly. However, archery is not meant to strengthen muscles. One must draw the bow by moving without intent. The breathing method for this is as follows: Press your breath down gently after you breathe in so that the abdominal wall is tightly stretch, and hold it there. Then breathe out as slowly and as evenly as possible (hum a note to practice releasing evenly until you’re out of air). After a short pause, draw a quick breath of air again. The master could not emphasize the importance of this breathing enough. In archery as in both Qi Gong and Tai Chi, if you don’t have control of the breath, you have nothing. By breathing, you bind and combine; by holding your breath, you make everything right; and in breathing out, you loosen and complete by overcoming all limitations.

The shot is a different story. To loose the shot, one must release effortlessly, unconsciously, like a baby grabbing a finger only then to release and reach for something else. If you release with your fingers or your shoulder, you cannot find the perfect shot as you have not let go of yourself. You do not wait for fulfillment but wait for failure. What stands in your way is that you have too much willful will. You think that what you do not do yourself does not happen. Master archers say with the upper end of the bow the archer pierces the sky. With the bottom end, as though attached by a string, hangs the earth. For purposeful and violent people the rip of the thread becomes final, and they are left in the awful center between heaven and earth.

To become a master, walk past everything without noticing it as if there were only one thing in the world that was important and real, and that is archery. The demand that the door of the senses be closed is not met by turning energetically away from the sensible world, but rather by a readiness to yield without resistance. The soul needs an inner hold, at it wins it by concentrating on the breath.

In preparing to perform the task of shooting, stick to mindful preparations. These purposeful preparations put one in the right frame of mind for creating. The meditative repose in which he performs them gives him that vital loosening and equability of all his powers… that collectedness and presence of mind, without which no right work can be done. Furthermore, beware of the danger of getting stuck in one’s own achievements. Do the task for its meditative purposes rather than validation. All right doing is accomplished only in a state of true selflessness.

Be like a bamboo leaf under the weight of snow. The leaf bends until the snow effortlessly slide off without the leaf having moved. A technical solution will not be able to transform into effortlessness but must be accomplished through releasing of the self. The bow will then shoot itself. After “right” shots, the breath glides effortlessly to its end, whereupon it is unhurriedly breathed in again. To gather the strength to draw back the bow, one must reach far enough spiritually. You must act as if the goal is infinitely far away. Upon releasing the shot, detach from the result and rejoice as if another has shot, for it was not you who shot it but rather your unconscious connection to the source, the Tao.

The ultimate purpose of this meditative art is to learn to release the self and connect to the nameless force that binds us all. For us, this can be applicable to sports, business, and to personal relationships. The goal here then is not the end result of hitting the target but rather in trusting our unconscious in completing our actions. This is why this book and its teaching are so powerful and profound to me.

hello, your post is very good.Following your articles.